The 1980s–1990s begin with a sense that everything has already been done

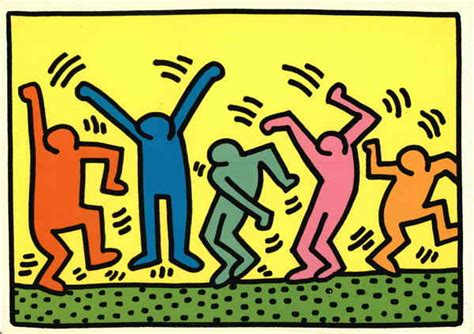

Postmodernism dismantles art into quotations and formats. The point is not to invent "an entirely new language" but to show how existing ones work. Paintings continue to be made, but installations, performances, objects, video, and photo series matter more and more. An artist can take a ready-made advertising slogan, logo, neon sign, packaging, a fragment of a TV series, their own body or apartment, and turn it into a work — not disguising the source but emphasizing it.

High and low are deliberately mixed: the aesthetics of supermarkets, nightclubs, TV commercials, and MTV end up in the same halls that once housed only "great" canvases. A single visual statement can comfortably contain a logo, a religious symbol, a news fragment, and an early precursor to the selfie. Art less and less pretends to be an autonomous world and more and more presents itself as a montage of what already fills the collective eye — screens, signs, magazines, logos. It is in this environment that the idea gradually takes hold: a person's image can also be assembled like a collage of styles, brands, and ready-made roles.

In the 2000s–2020s, the digital environment is added to this

As we recall, at the beginning of the twentieth century, artists taught us to look at an image as a construction of forms and color patches: what matters is not "what is depicted" but how the field is organized, how the eye moves across it.

In the second half of the twentieth century and into the twenty-first, this logic simply changes scale. Photo, video, AR, online projects become not "illustrations to art" but the field of work itself. The screen and social networks are another exhibition space. The painting is no longer the main form: what matters more is how the viewer moves through space, what the camera captures, which fragments end up in the feed, and how all of this spreads across media. If before we traced the path of the eye within the rectangle of a canvas, now the object becomes the path of the body and avatar within an endless grid of screens — the same idea of construction, only now assembled from clips, street photography, stories, and logos.

Color works as brand code and screen light

Color in art and fashion of this period is less and less connected to "nature" and more and more to the media environment.

Neon signs, RGB screen palettes, corporate brand colors, acid-bright sports palettes, pastel social media filters — all of this influences how we perceive clothing and objects. Major artists and designers consciously take ready-made color codes — red "like that brand," blue "like that social network," yellow "like a warning sign" — and use them as a language.

Textiles: global supply chains, technical performance, and speed

Fabric is no longer a local story. Cotton, wool, synthetics, functional membranes, and elastic fibers pass through several countries: one provides raw materials, another spinning, a third dyeing, a fourth assembly. Fast fashion and luxury often travel similar routes, differing not so much in geography as in the amount of handwork, quality control, and marketing.

Technical fabrics — membrane jackets, stretchy sportswear knits, breathable sneakers, water-repellent coatings — turn clothing into a tool of endurance and performance: you need to run, fly, work, train in these. The same materials easily transition into everyday wardrobes: tracksuits move onto the street and into offices, puffer jackets and fleece become the norm.

Textiles are less and less about "beautiful material" and more and more about the interface between body, climate, and urban rhythm. Color here also works as navigation: by the shade of sneakers, a running jacket, or a streetwear hoodie, one can easily read the brand, the scene, and even the context in which the look exists — office, neighborhood, fitness club, or social media feed.

Dress codes: luxury as logo, sport as foundation, streetwear as the new formal language

In both men's and women's clothing, the suit in its classic form loses its monopoly.

In the 1980s and beyond, the expensive suit becomes one variant of the top executive's "armor" rather than the universal norm. In parallel, the idea of luxury as logo emerges: a bag, belt, sneakers, or puffer jacket with a large brand emblem becomes a stronger status signal than any carefully tailored cut without insignia.

Fast fashion copies the runway almost in real time, making any silhouette short-lived and accessible. Streetwear brings hoodies, sneakers, baseball caps, and bomber jackets to the forefront; sportswear becomes the normal foundation not only for weekends but also for offices with "casual" and "smart casual" codes. Sneakers, T-shirts, and sweatshirts migrate into spheres where formal shoes, dress shirts, and blazers were recently required.

At the same time, what was once anti-elite — skate, hip-hop, street subcultures — gradually integrates into luxury: brand collaborations with artists and street labels, couture sneakers, capsule collections for fans.

High and low codes mix: expensive suits are worn with sneakers, sports fabrics appear in high-end coats, luxury logos live on shapes that recall workwear or streetwear.

Digital image and clothing "for the camera"

To all this is added another dimension that previous eras did not have: clothing exists not only on the body but also in the frame.

Decisions about what to wear increasingly pass through the thought "how will this look in a photo/in stories/on a Zoom call." Texture, color, silhouette must read not only up close but also in the small rectangle of a screen. A brand logo, a bright element, a distinctive silhouette help one be recognizable at a distance of just a few pixels.

This also changes the relationship between "real" and "performed": the same hoodie, sneakers, or bag can be worn for years, but in the feed it appears as a series of edited versions of oneself. Clothing becomes part of a personal brand, not just social status; dress code becomes part of platform and audience rules, not just office or street.

In the end, brand and camera become new intermediaries between a person and their image

Art of recent decades works with brands, media, the body, and environment as a single set of materials and blurs the boundaries between "advertising" and "critique of advertising," between personal gesture and content. Textiles and clothing exist in the same logic: global supply chains, technical fabrics, capsules, drops, limited collections, brand as a sign of belonging.

The era of globalization and media has offered a convenient illusion: instead of a complex, shifting "self," one can present to the world a set of recognizable signs — and people and algorithms alike will understand it without unnecessary questions.

Psychologically, this provides a quickly replaceable prosthesis of identity: a ready-made way to feel "put together," recognizable, and belonging to some group, even when inside everything is far less stable and does not fit into any logo or set.

Digital platforms reinforce the chosen image through likes, saves, and reach: if a certain style "works," it becomes hard to let go of, even when inside you are already different. A subtle internal conflict emerges between the living, changing "self" and the stable avatar that followers and algorithms expect to see. The fear of losing response and recognition pushes one to hold onto the same set of items and angles, and clothing transforms not only into a language of belonging but also into a way of not breaking the script that seems to have already been written for you.