This text is the finale of the project "The History of the Visible Self: From Icons to Instagram"

Here we look at art and clothing as a single shared mechanism: how through paintings, fabrics, and dress codes, humans learned to understand who they are and "how to be visible."

In each period, we examined the same connections:

- what artists learned to do with images,

- which paints and fabrics became available,

- how this turned into rules of appearance — especially in women's clothing,

- and what psychological knot was ultimately tied: what was considered normal, proper, modern, "one of us."

We drew on the history of art and costume, research on color and textiles, histories of social codes and fashion — but not to retell a textbook, rather to see the line in its entirety: from the golden divine background and rigid roles to the image "for the camera," assembled from logos and filters.

Below we will summarize how exactly this line passed through the centuries and what it does to our sense of self today.

In the medieval world and before 1500, clothing was essentially a sign above one's head

In the world before 1500, clothing and image work in unison: both reinforce order. Paintings show saints, rulers, and townspeople in their "proper" shells; fabric, color, and cut in real life duplicate this division. Handmade textiles and a limited palette of dyes strengthen the sense of predetermination: if you simply have no legal access to a certain color and material, then psychologically you are also "not allowed" there.

Internal doubts in this system interest few people. The main thing is that the cloak, headdress, and jewelry unambiguously declare who you are. Clothing provides simple support: a person knows their place and sees where their boundary lies — literally at the edge of the mantle. A person wears what they are entitled to by law and goes to war by order for the same reason: this is how the surrounding order is structured. The divine is concentrated in the gold and radiance of the image; everything else, the personal, remains almost flat, inexpressive, unworthy of special attention.

In the 16th century, air first enters this rigid system

In the 16th century, artists learn to construct convincing space, body, and light as a well-tuned system. The image becomes predictable: if everything is done "according to science," the viewer will believe. Simultaneously, textile and dye production grows, and the choice of materials expands somewhat.

Psychologically, this gives a new sensation: if a painting can be planned so precisely, then one's appearance can also be assembled, not just inherited.

In the game of self-fashioning (constructing oneself through clothing), a person begins not only to be but also to appear — as a scholar, courtier, or "risen" townsman. The code still works, but within it, play emerges.

In the 17th century, the world increasingly becomes a stage

Painting learns to control attention through light and shadow, to highlight some faces and hide others, to make fabric glint or sink into darkness. Costume works as part of this direction: dense fabrics, deep colors, a rigid construction of the silhouette.

Psychologically, this is the century when the image must be impeccable and weighty. A person is expected to hold their role — as a believer, loyal subject, head of the family, "a person of honor." Inside there can be anything, but on top of this must lie a heavy, properly assembled image. The dress code stops being simply "I am" and increasingly becomes "I must appear" — and the gap between these two points becomes noticeable for the first time.

The 18th century: pastel lightness as a carefully crafted effect

In the 18th century, air and light become as important as the people themselves. Paintings fill with soft transitions, bright interiors, garden scenes; paints and fabrics shift to pastels — gentle pinks, blues, creams, "powdered" shades. The production of silk, lace, and fine fabrics makes it possible to create a surface that is weightlessly festive: a dress looks like a cloud, a wall like a light stage set.

Psychologically, this is the century when a person is expected not just to play the right role, but to display visual lightness. One must look carefree, elegant, "natural," even if behind this stands a heavy corset, a multilayered dress, and a long list of prohibitions. The more pastel and airy the scene appears, the stronger the pressure to always be in tune with this picture — not showing the effort, the cost, and the exhaustion beneath the layers of silk and powder.

The 19th century replaces decoration with respectability

In the 19th century, everything accelerates: cities, transport, work, flows of people. Art begins to capture not so much "how things should be" but "how things look right now": fog, smoke, lights, movement. Simultaneously, factories and shops establish mass production of fabrics and ready-made clothing; people of different classes increasingly find themselves mixed together — in trains, on boulevards, in offices, in new neighborhoods.

Psychologically, this creates a new ideal — respectability. The dark suit and neat dress promise not only a certain wealth but also a "decent character" behind them. The problem is that this shell becomes accessible to increasingly diverse people. The same silhouette can conceal both a stable life and a complete lack of foundation. We continue to trust the image as proof of reliability, even though technically it has long since become a mask that can be bought without changing one's actual position.

The early 20th century adds to this the requirement to be dynamic

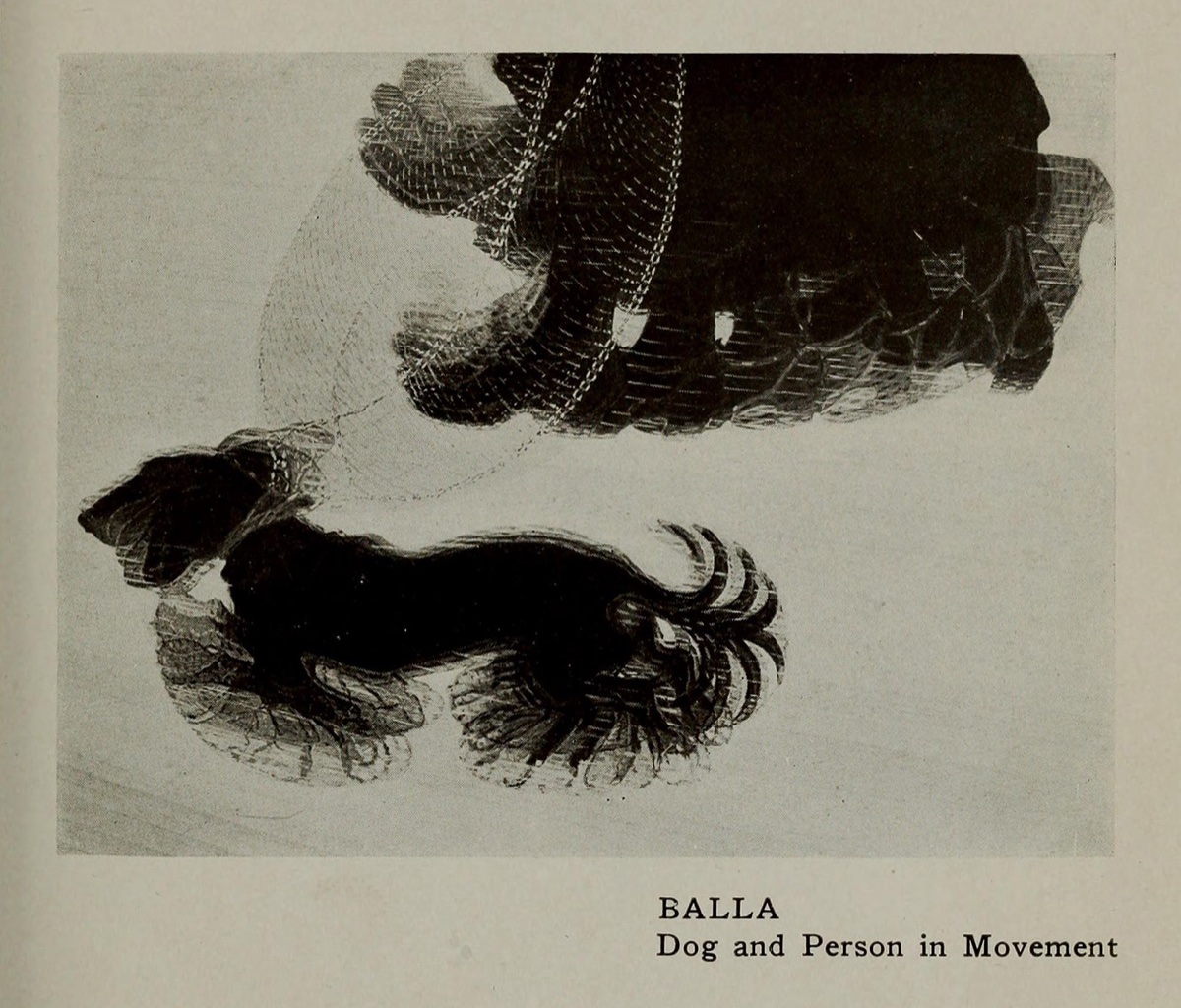

At the beginning of the 20th century, artists become increasingly interested not so much in verisimilitude as in the optics of perception itself: how the eye assembles form, how the gaze moves across a surface, what gestalt emerges from lines, spots, and color.

The movement of the eye across a painting and the movement of the eye across a clothed body begin to work the same way: the faster and more easily the gaze glides over an image, the more mobile and swift the person themselves appears to us. Movement in all its manifestations becomes the everyday modern norm.

And so a new framework is born — to be dynamic means to be modern. A straight silhouette, shortened hem, comfortable shoes, and a simple palette become not only a matter of convenience but also a test: are you a person "of your time" or stuck in the past? A woman is offered freedom of movement and work, but is expected to remain within the bounds of "good taste"; a man is required to be functional and composed.

Psychologically, we move from "be proper" to "be current." If in the past clothing had to confirm moral and social "correctness," now it must also prove that you live at the right tempo and haven't gotten stuck in the past. Both are still rigidly controlled by the external gaze — only to the fear of appearing improper is added the fear of looking outdated, "not of this time."

After 1945, clothing and image take on the role of a painkiller

Painting honestly shows anxiety, disintegration, the scream — grand gestures, fields of color, figures on the verge of disappearance. Clothing, on the contrary, assembles a comforting set: the gray flannel suit, the "proper" emphatically feminine dress, the new synthetic material that won't let you down.

Psychologically, this is a quiet agreement: even if inside, the world has barely survived catastrophe, if on the outside everything is neatly pressed, one can at least temporarily pretend that life has normalized. We still read a suit or dress from the 1950s as an image of "healthy, proper life," even understanding how much was left unsaid within it.

In the 1960s–1980s, clothing for the first time becomes a mass language of choice and tribe

In the second half of the 20th century, art accepts the image-saturated world as its starting conditions: pictures can be endlessly quoted, multiplied, repainted. Mass production of textiles and clothing does the same with appearance: jeans, T-shirts, jackets, suits, and dresses exist in enormous quantities and combinations.

Psychologically, clothing for the first time becomes a mass language of free choice of belonging. If you want to be "one of" the hippies, punks, office workers, disco fans, or rockers — you put on their code. The very fact that it is enough to buy a certain item to visually integrate into the desired group gives a sense of support: even if the world is unstable, one can at least belong to some tribe through clothing. This is both consolation and a tool of self-determination simultaneously — and the system quickly learns to sell any rebellion as a new style. And in this, a new knot is tied for subsequent generations: the fear of falling out of the tribe transforms into a constant internal demand to renew oneself through purchases, otherwise one seemingly disappears from the radar of "one's own" world.

From the 1980s to today, brand and camera stand between a person and their image

Logos, silhouettes, sneakers, hoodies, the "right" glasses, and successful photographs form a new alphabet from which one can quickly assemble a version of oneself for the world and for algorithms.

Art works with the same elements, showing how conditional these signs are, but in everyday psychology they are convenient: it is much easier to manage a set of symbols than to deal with a living, contradictory "self." Brand and frame give the feeling: if my outfit is recognizable, then I am understandable, I have a place — in a group, in a feed, in a city.

This is a quickly replaceable prosthesis of identity: it gives a sense of being put together and belonging, even if inside everything is far less stable and does not fit into any logo or set.

If you look at this line as a whole, the path looks like this

from clothing as a rigid sign of place → to clothing as a way to assemble a role → to clothing as a quick ticket into a tribe → to clothing as a prosthesis of "self" for the camera.

And the question that remains is quite simple and uncomfortable: if we turn off this prosthesis — the brand, the dress code, the flattering lighting — who do we then meet, and what material for a new "visible self" will we have to invent next?

SO WHO AM I?

Recommended books:

Malcolm Gladwell — Blink: The Power of Thinking Without Thinking

Victoria Finlay — Color: A Natural History of the Palette

Richard Thompson Ford — Dress Codes: How the Laws of Fashion Made History

Victoria Finlay — Fabric: The Hidden History of the Material World

Virginia Postrel — The Fabric of Civilization: How Textiles Made the World