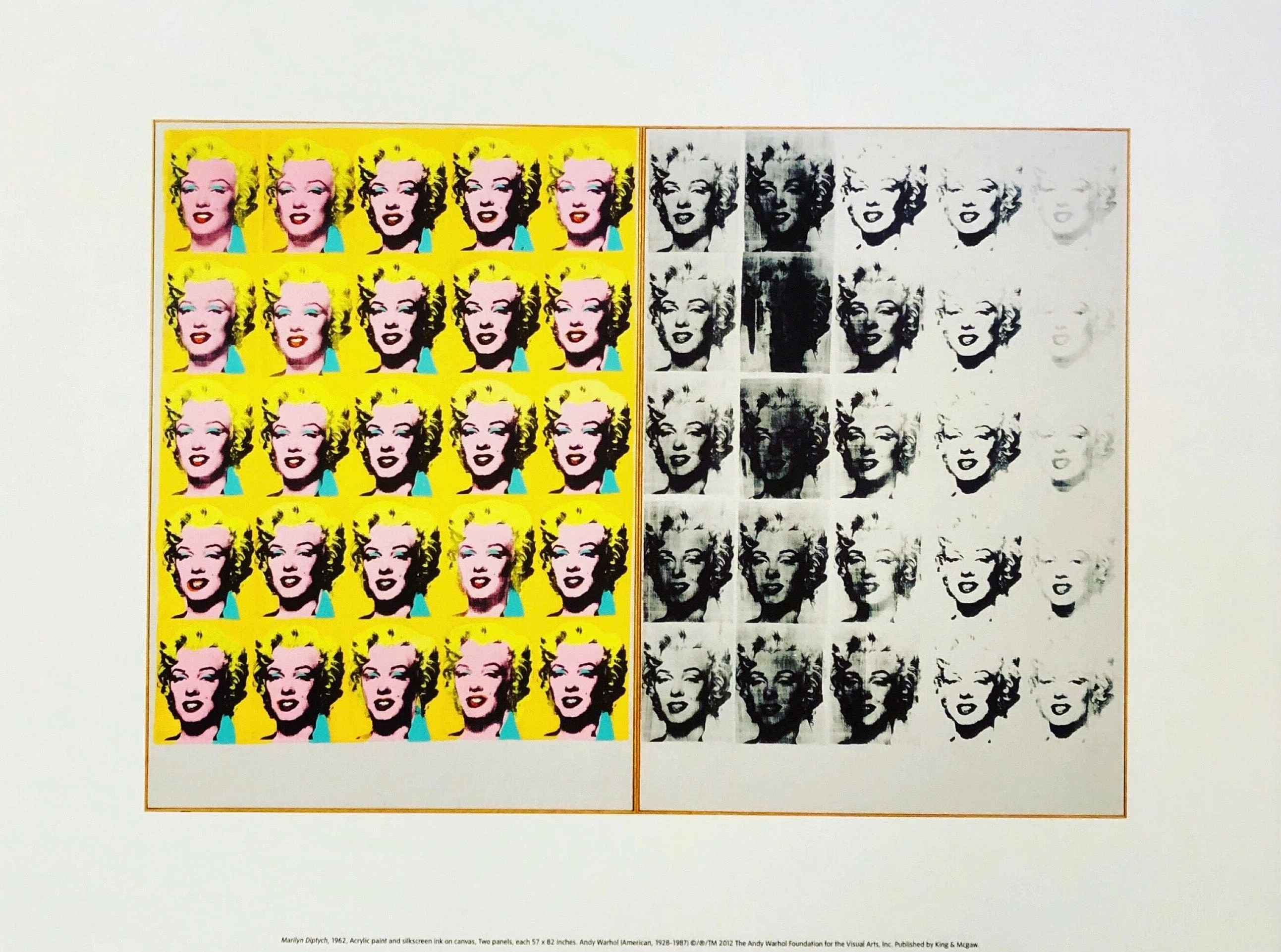

The 1960s–1980s — a time when art finally acknowledges: the world is overflowing with images, and they can not only be created but also repeated, cropped, recolored

Warhol multiplies a soup can and Marilyn's face to infinity, Lichtenstein enlarges comics to the size of paintings, Rosenquist, Hamilton, and other pop artists take advertising, cinema, and print as their working material. In parallel, minimalists, pop art, conceptualists, performance, and video art deconstruct the very structure of art: what counts as a work, where the boundary lies between object, text, action, and documentation. A painting is no longer required to be a "window" or an "authorial gesture" — it can quite easily be a fragment of a mass image, pulled from the stream and shown as is.

Color works as a signal of belonging

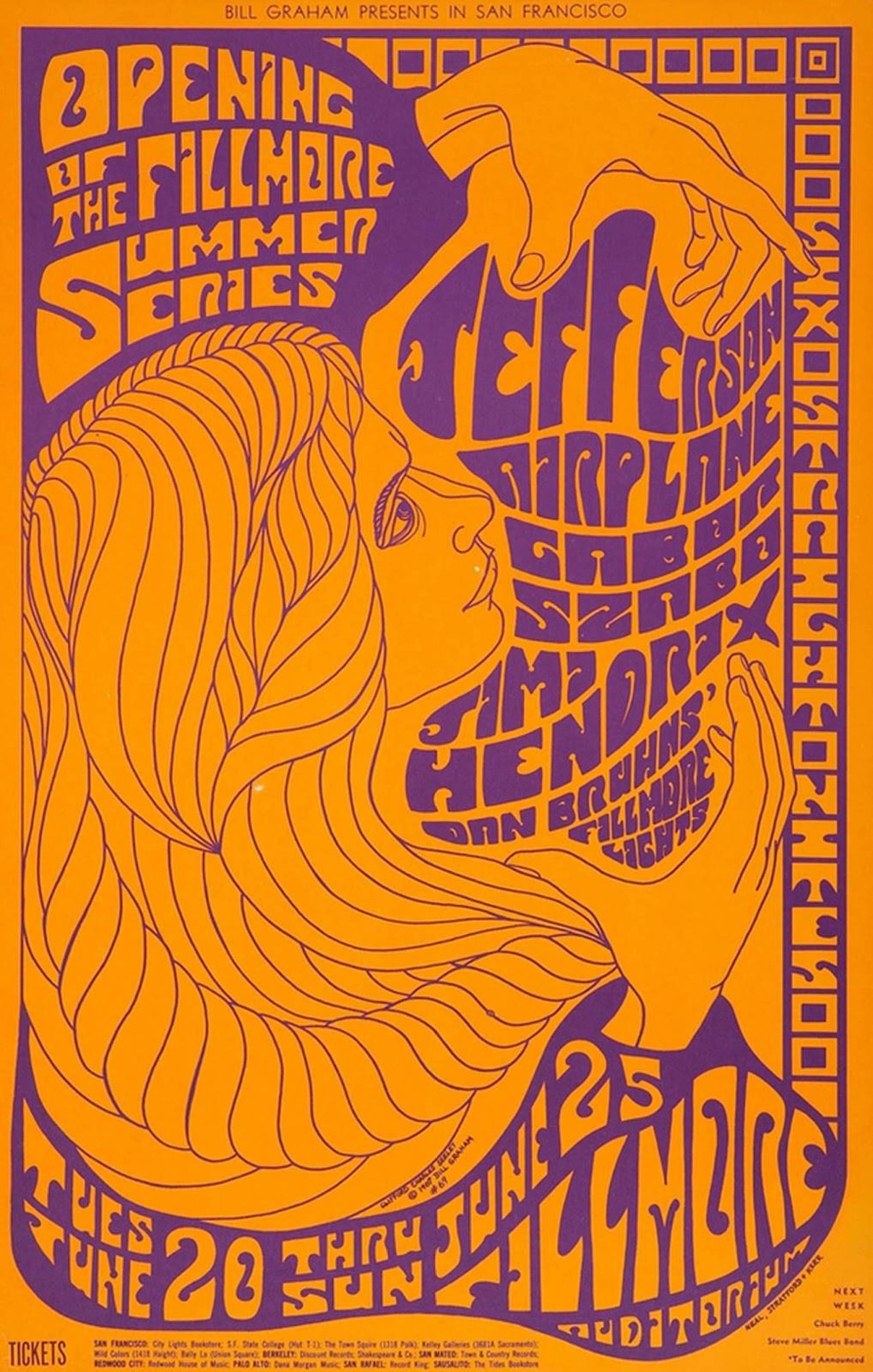

The palette is taken directly from the industrial and media world. These are the print triads of advertising posters, neon signs, acid hues of psychedelic posters, optical contrasts. Color does not disappear from painting — on the contrary, it becomes aggressively visible, flat, almost poster-like. Bright red and yellow scream like a logo, the black-and-white stripes of pop art literally shimmer before the eyes, pure blue and orange blocks are readable from a distance.

Textiles: from simple material to carrier of logos, prints, and positions

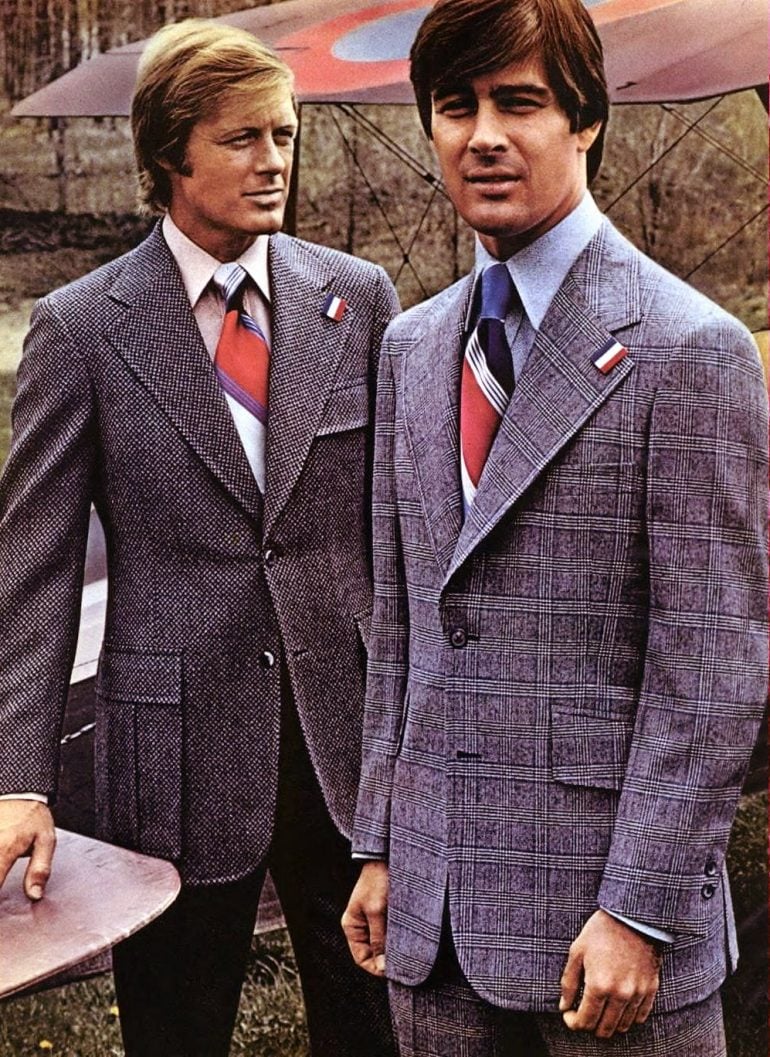

In fabrics and clothing, stable bright synthetic dyes, fluorescent shades, and prints that can be reproduced in batches all appear simultaneously. What was recently a rarity (very pure violet, toxic green, vibrantly bright orange) is now available as a shirt, suit, or sports jacket. Color ceases to be only "pretty/not pretty" — it increasingly means "one of us" / "one of them": hippie, disco, punk, office, uniform.

Denim — originally a workwear fabric with stable indigo — transforms into a global basic material: jeans are worn by teenagers and rock stars, students and office workers in informal settings. The fabric with its characteristic fading dye texture becomes a symbol of both freedom and mass appeal at once.

The cotton and jersey T-shirt transitions from underwear to outerwear and becomes the ideal surface for printing: band logos, political slogans, brands, art prints.

Textiles for the first time openly carry text and image on themselves, and this is as important as the cut itself.

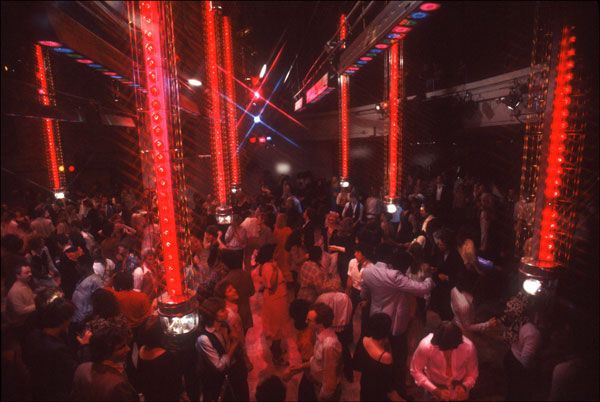

Polyester and other synthetic fibers make it possible to produce shiny, bright fabrics for disco, tracksuits, and waterproof outerwear. Fabric is no longer only "about how it drapes" but also about what is written on it, how it shines, and which scene it belongs to — stadium, club, street, office.

Dress codes: work, mass everyday life, and the explosion of subcultures

The official line is quite recognizable: the office and business suit adapts, becomes slightly less formal, options appear without a hat, with narrower lapels, lighter fabrics, but the general code of "dark bottom, white shirt, tie" still holds.

For women — suits with skirts, sheath dresses, blouses, neat heeled shoes; later — pantsuits, but still with a cautious set of restrictions.

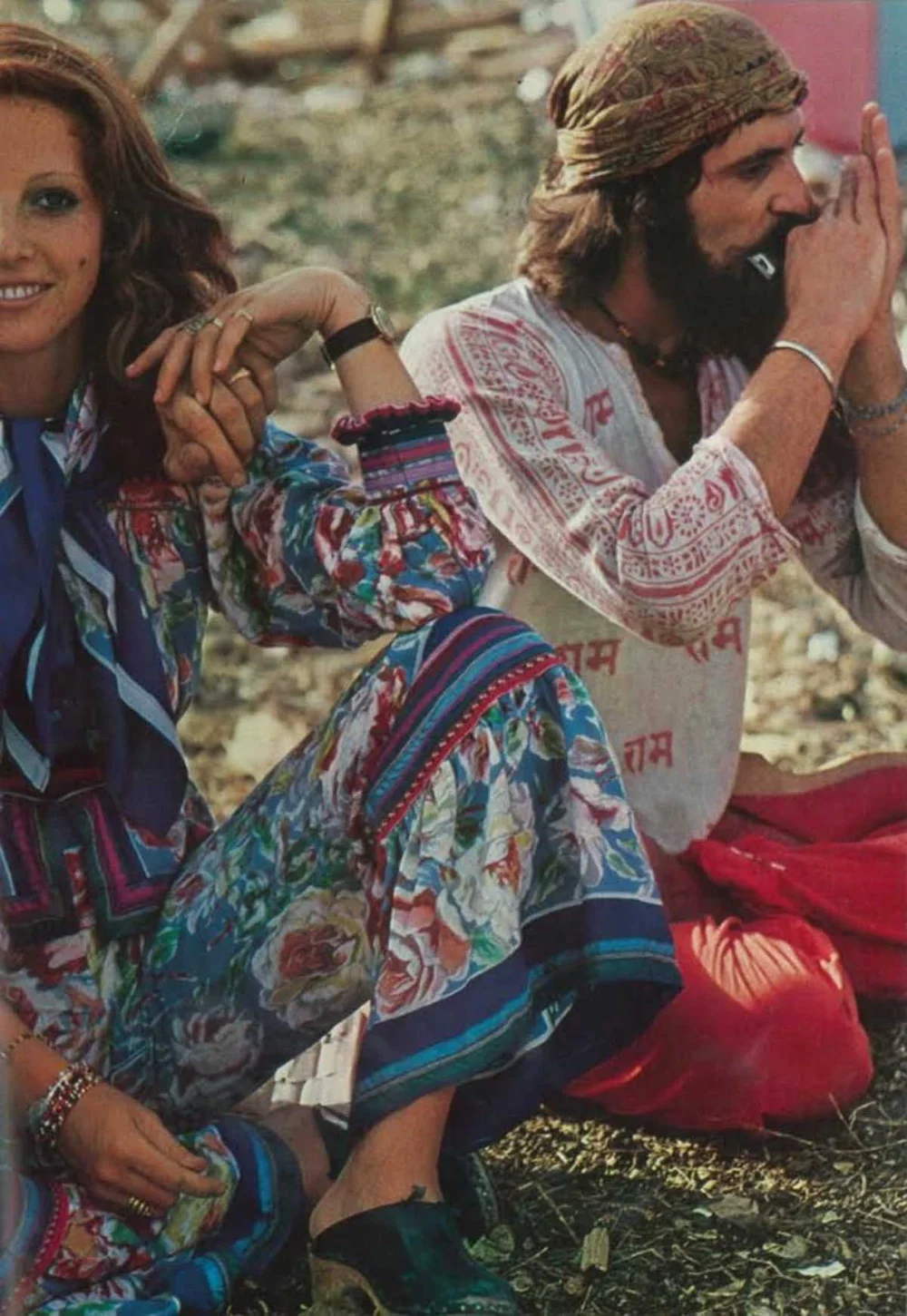

Alongside this, and sometimes in direct conflict, the world of subcultures grows.

Hippies — long hair, ethnic fabrics, embroidery, jeans, leather cord and bead and flower decorations. Mods and rock and roll — narrow suits, minimalist coats, clean lines, carefully chosen boots. Punk — leather, studs, torn denim, spikes, deliberately aggressive prints. Disco — shiny synthetic fabrics, tight silhouettes, high heels, heavy makeup.

In these decades, clothing for the first time massively becomes not just a sign of class or profession but a statement about whose side you are on: "normal life," protest, "peace and love," "nothing is sacred," "I'm from the club, not the office."

And at the same time, the market very quickly learns to sell any protest as a style: what started as a gesture against the system can, a couple of seasons later, sit on store shelves as a "fashionable jacket" or "jeans with ready-made holes."

In the end, clothing turns into a language of choice that immediately becomes part of the shop window — and part of the system of reassurance

Art of the 1960s–1980s works with mass images like building blocks: cutting, enlarging, multiplying, arranging on shelves. Clothing does the same with roles and moods. Jeans, T-shirt, sneakers, leather jacket, formal blazer, shiny disco dress — all of these become quickly readable lines: "I belong to this music," "I'm from this neighborhood," "I don't share your rules," "I prefer stability."

If before 1500 clothing was more like a sign above your head — you wore what was prescribed for your place, and there was almost no choice — now there arises a sense of freedom: it is enough to buy the right things to rewrite your "badge" and cross into another world. The very fact that you can simply put on a specific code and visually integrate into the desired pack creates a foundation: even if the world is unstable, you can at least feel that you are not alone and that somewhere "your people" are waiting for you.

Subcultural codes are initially born as an attempt to honestly find "your people" — by music, views, way of living. But as soon as these codes enter mass production, belonging must be confirmed again and again: with new jeans, sneakers, patches, records.

Psychologically, a new knot is tied here: the fear of falling out of the pack transforms into a constant internal demand to renew yourself through purchases, otherwise you seem to disappear from the radar of "your" world.

Next part of the project - 1980s–Present: Environment in Art, Brand in Clothing