After 1945, painting almost entirely ceases to explain itself through subject matter

Pollock, de Kooning, Rothko, Newman, Kline, sometimes Giacometti and Bacon — each in their own way — demonstrate that the canvas can be a field of gesture, stain, and breath, rather than a stage with characters.

In Europe, the postwar figure is often thinned, elongated, vulnerable; in America — dissolved in masses of paint. The painting becomes a way of enduring what cannot be put into words: the experience of war, the Cold War, the nuclear threat, the reassembly of the world.

The painted canvas transforms more into a field of states than an illustration: large format, the gesture of the brush, drips, clumps of paint, or even color fields work as a direct trace of tension, emptiness, fatigue, or suppressed horror. The viewer is invited not so much to "read a story" as to stand before this field and feel in their body what it is like — to live in a world where everything is being outwardly reassembled while inside there remains the feeling that there is no longer any foundation.

Color works as field and temperature, not merely as hue

The artist's palette has long ceased to be limited to earth and minerals: there are stable synthetic pigments, lacquers, industrial paints. Rothko paints soft rectangles of color that do not "denote" things but set a state — dense red and violet thunder, dark blue falls away, yellow warms or blinds. Newman draws a single vertical stripe — zips — and makes us feel how color "breathes" on either side. Even when paint drips, flows, and splatters, there is always a choice of temperature behind it: cold/warm, heavy/transparent, muted/ringing.

At the same time the surrounding world fills with other colors: automobile enamels, refrigerator and kitchen lacquers, new plastic objects, synthetic fabrics. Color ceases to belong only to the artist and the textile market — it becomes part of the comfort industry, and this is felt both on canvases and in wardrobes.

Textiles: synthetics, convenience, and the promise of "new life"

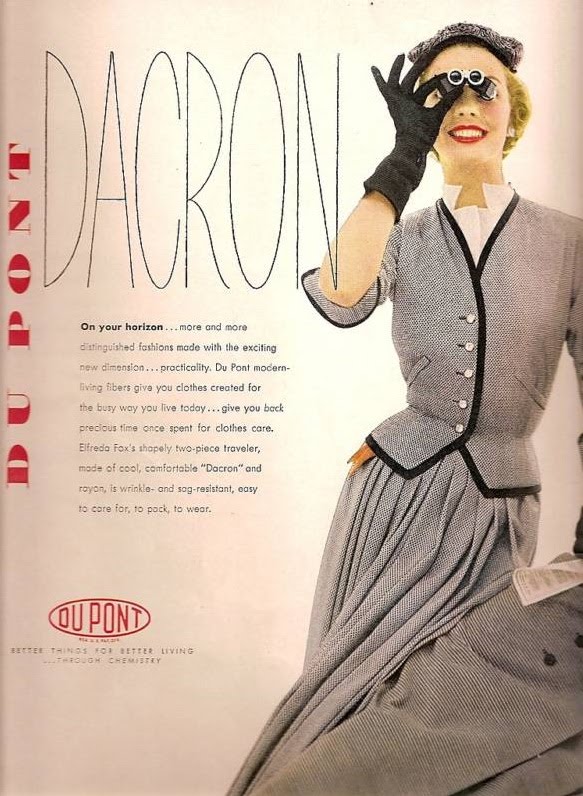

Synthetic fibers move from military needs into everyday life. Nylon, early polyesters, acetates enter stockings, dresses, linings, undergarments. Easier to wash, faster to dry, less prone to wrinkles — this is sold as part of the new happy life: home, refrigerator, automobile, and "wrinkle-free" fabrics.

Industrial knitwear and ready-made clothing consolidate their dominance: sweaters, cardigans, T-shirts, tracksuits are no longer just for sport. This is still not "high fashion," but already the norm for weekends and leisure.

In parallel, haute couture (Dior, Balenciaga, and others) works with expensive wools, silks, taffeta, tulle — but they too gradually begin to account for new materials and the new figure.

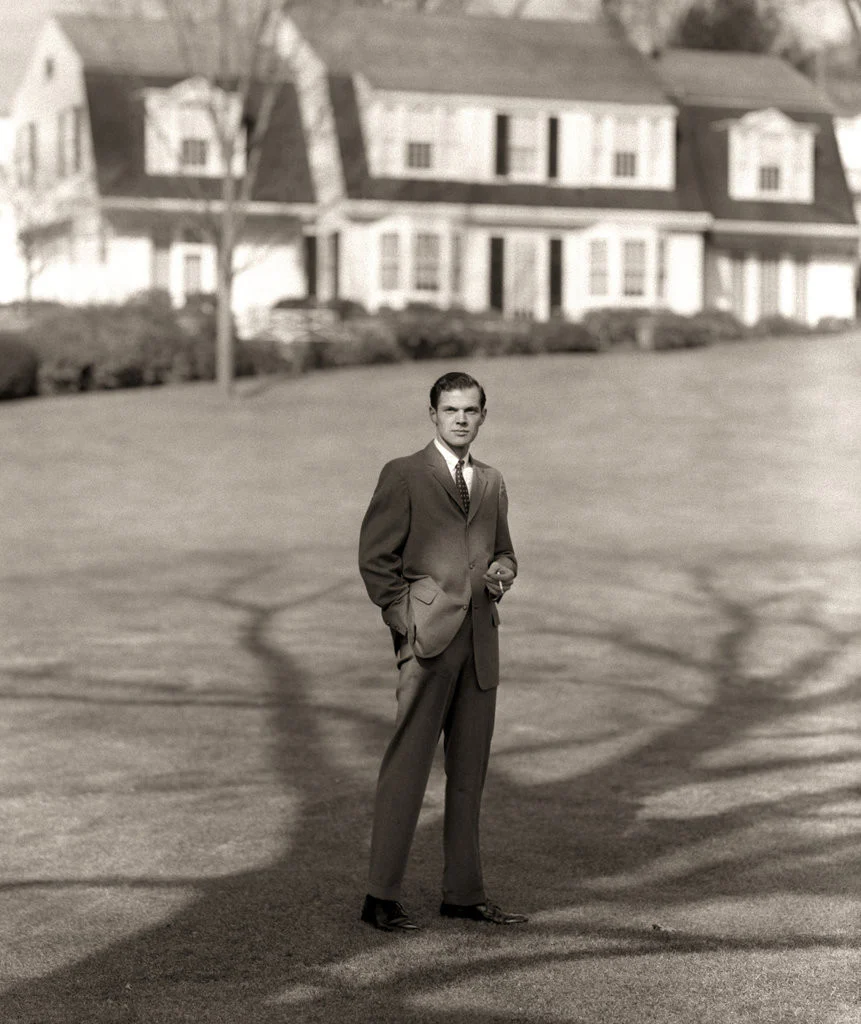

Men's dress codes: the gray suit as a comforting shield

For men, postwar fashion is formally unspectacular but psychologically powerful. The gray flannel suit becomes an icon: the office man in a neutral jacket and trousers, white shirt, understated tie, hat — a maximally "normal," safe image. After military uniforms and chaos, it feels good to resemble others, to "dissolve" into a group of the same safe office people.

Corporate culture embraces this idea: the suit should not make one stand out but prove that one fits in. Color moves into the danger zone: too bright a tie or suit is already "too much self." The fabrics themselves also change: synthetic fibers are added to wool, making care easier and reducing creasing. The result is a middle-class uniform: practical, not too expensive, easily replicated, and yet painfully similar to a "real" suit from a fine tailor.

Women's clothing: between a return to "femininity" and real experience

The women's wardrobe, by contrast, is initially rolled sharply backward — from the standpoint of freedom of movement. In 1947, Dior presents the New Look: a narrow, accentuated waist, a full skirt with enormous fabric consumption, soft shoulders, neat gloves and hats. After the war years, uniforms, rationing, and work overalls, this reads as a celebration and a return to "normal life." But at the same time — also as a return to an ideal where the female body must be composed, soft, "domestic," inscribed into the image of wife and mother.

Other designers join in: shapewear, bras, accentuated bust, hourglass figures — all this once again requires particular posture and specific behavior. This silhouette becomes the norm of respectability for many professions where women are admitted "on condition."

In parallel there exists another line: practical clothing for work, for the city, for teachers, secretaries, nurses, for women who do not intend to return to a solely domestic role. More straight-cut coats appear, suits with skirts, simple blouses, sweaters. A bit later trousers and more relaxed silhouettes will be added, but already in the 1950s the internal crack is noticeable: the advertising image of the New Look and the actual day of a woman who commutes to work by bus and does her own laundry do not always coincide.

In the end, postwar "normality" rests on the grand gesture in art and the neat uniform in clothing

The abstract canvas where paint pours and splatters, and the shop window with neat suits and dresses, speak of the same era — but of different sides of it. Painting permits itself to scream, tremble, break into stains, to acknowledge anxiety and helplessness before the scale of catastrophes; clothing, by contrast, offers a comforting image: a neat suit, the right dress, a new synthetic material that will not let you down.

Smooth silhouettes, easily washable fabrics, and predictable forms provide not only convenience but also the feeling that, unlike history, clothing can be controlled: it does not fall apart, does not flow, but serves as it should. This creates a quiet hope that life too can be brought into such order: if everything is ironed and clean on the outside, then surely the chaos inside must somehow come together. Any "wear marks" — a stain, a snag, a rumpled suit — begin to be perceived not merely as carelessness but as a breach in this fragile illusion of control.

It was precisely in these years that a visual language was invented where outward order and cleanliness were meant to obscure the experience of radical instability — and we still read that order as a promise, even when we know how turbulent everything hidden beneath it can be.

Next part of the project - 1960–1980s: Mass Culture in Art, "Uniqueness" in Clothing