Art openly acknowledges: depicting things "as in life" is no longer obligatory; what matters more is how the image itself is constructed

Matisse simplifies objects to patches and lines, leaving only the essential. Picasso and Braque in Cubism break down bodies and objects into facets and planes, showing them simultaneously from multiple viewpoints. Kandinsky and Malevich move into pure abstraction, Mondrian reduces everything to a grid of lines and rectangles. Brancusi in sculpture removes details, leaving pure volume and rhythm.

The artwork ceases to be a window onto a reality of impressions and becomes a construction of form and color, where meaning arises from their relationships. If in the era of icons and altarpieces it was largely enough for viewers to recognize the subject and the saint — who stands before them and what story is being told — in the early 20th century this is no longer sufficient. Here what matters is how diagonals guide the eye, how color repetitions and the rhythm of stripes and rectangles work, what trajectory of movement across the painting they establish. The sensation from this movement becomes part of the content: we do not simply look "at" the image but seem to pass through a space. One must not just "recognize the subject" but assemble meaning from the trajectory of movement across the painting.

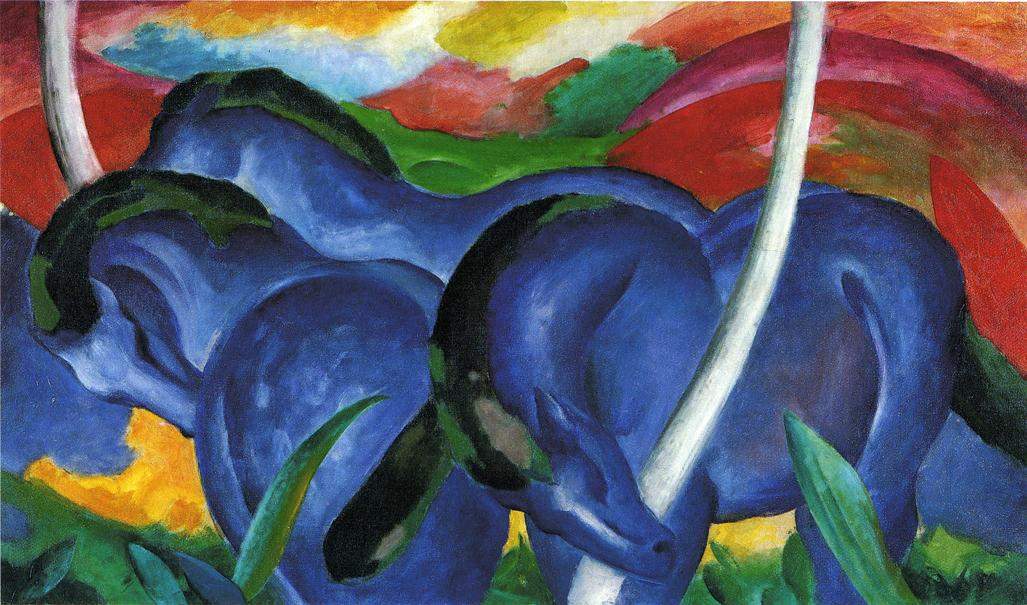

Color works as construction and accent

The palette still contains the same earth tones, mineral and chemical blues, reds, and greens, but the principle changes: what matters is not the "correct color of an object" but the interaction of patches.

The Fauves use almost pure, sharp shades — blue next to orange, red next to green — for the power of impression.

The avant-gardists limit the palette to several primary colors to build a logical system: red, yellow, blue in Mondrian; red-black-white in Malevich.

Color becomes an element of construction: rhythm, tension, and balance are read through it. Behind this stand new stable pigments and dyes that work identically in paint, fabric, and printing.

From here — a direct path to how we perceive a "stylish" look today

A well-assembled outfit reads like a small painting: 2–3 main colors, a clear rhythm of repetitions (for example, the same shade in shoes, bag, and a detail of the print), one accent tone and a calm background. We automatically see not "a blue dress and black boots" but the overall picture: is there an echo of shades, do the patches clash, does the look "tip over" to one side because of a color that is too heavy.

Early avant-garde literally teaches the eye to break down a unified color field into separate pieces and track how they balance each other. The same skill then calmly migrates into clothing design and personal style: dress, jacket, bag, shoes, and the city background are read as a set of color blocks that need to be coordinated. Stores, stylists, and visual platforms essentially continue this logic: capsule wardrobes are built from a limited set of basic colors plus a few accents; color blocking repeats work with large planes of color; "stylish" looks in the feed are easiest to read when the scheme is simple and assembled.

Even if we have never seen a Mondrian in person, we are already accustomed to evaluating an outfit by the balance of patches rather than the "correctness" of an object's color: a green skirt "works" not because green itself is successful but because next to it a white shirt, dark boots, and, for example, a small repetition of green in accessories sound right. This habit of seeing clothing as a small composition is a direct legacy of early 20th-century experiments with limited palettes and the construction of color.

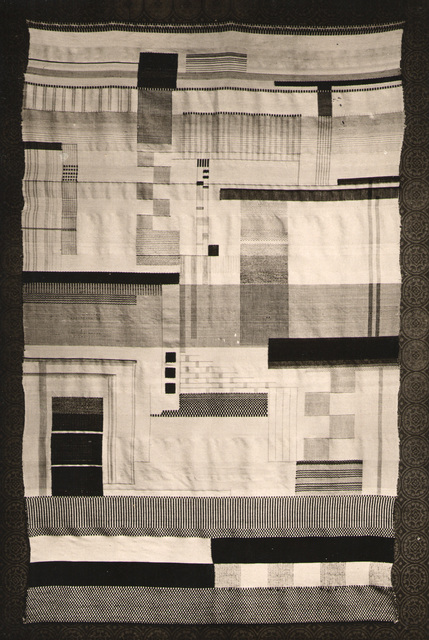

Textiles: from luxurious material to industrial material for life

Alongside traditional wool, linen, and silk, artificial fibers appear — viscose, early acetates, new ways of processing cotton. Fabrics become thinner, lighter, more elastic, easier to wash and cut.

In workshops such as the Bauhaus, textiles begin to be designed as part of architecture and the world of objects: stripes, checks, simple geometric motifs, minimal excess. This is already material with specified properties: how it drapes, how much it weighs, how it breathes, whether it will withstand sport, the office, travel.

Factories sew everything: from work overalls to inexpensive dresses and city suits. Printing, knitwear, and standardized patterns allow far more people to dress "in a modern way" than before. Fabrics cease to be merely a sign of status and increasingly become a tool of tempo: can you run for a train in this, work, dance, ride a bicycle.

Dress codes: modernity, functionality, movement

The men's suit retains the basic form of the 19th century — jacket, trousers, shirt, tie — but new roles emerge around it. There is a strict formal set, a lighter urban version, sportswear, uniforms for pilots, engine drivers, athletes. It matters not only to be "respectable" but also to look current, "not stuck in the past."

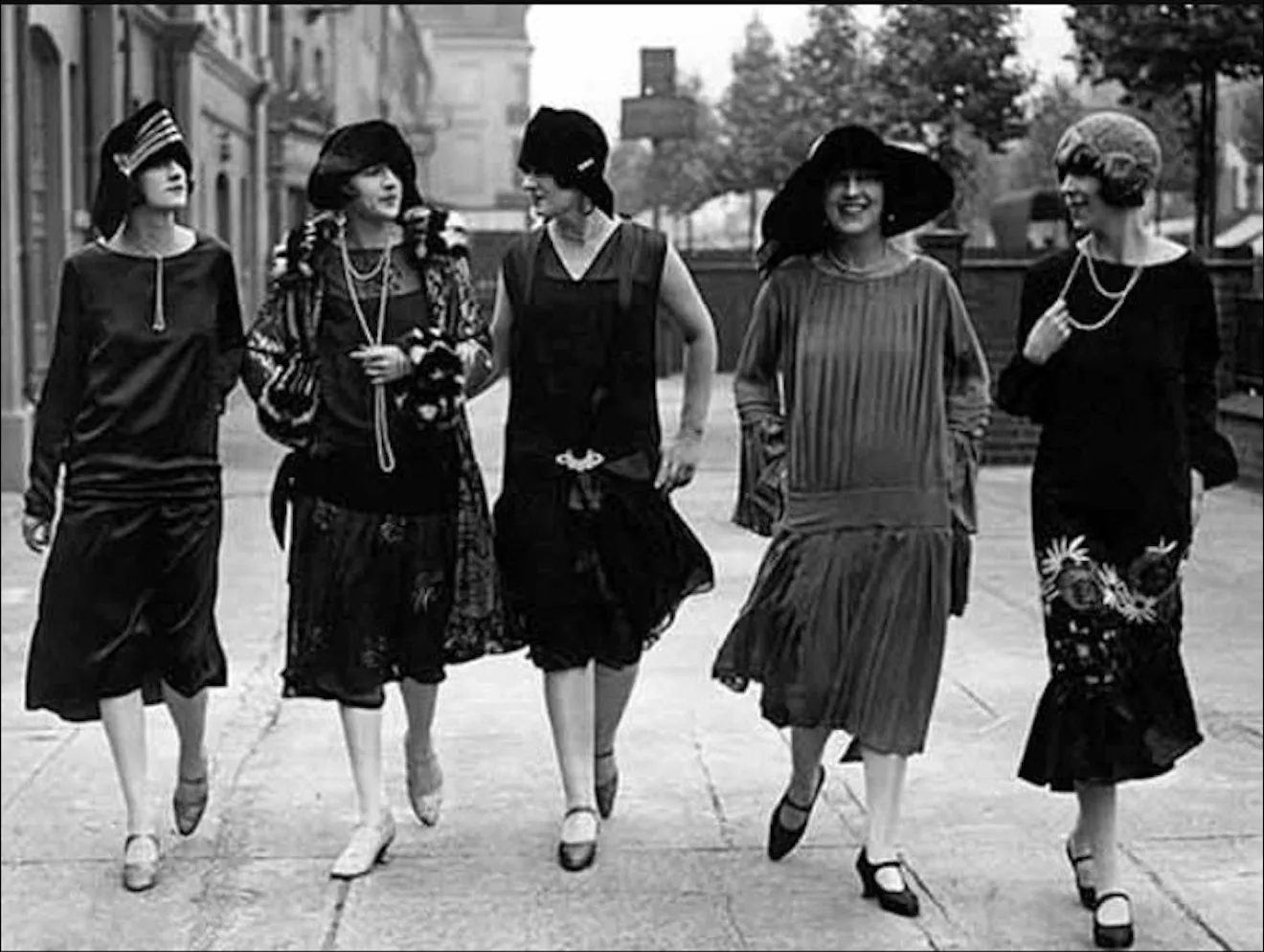

In women's clothing the changes are far more noticeable

The corset gradually loses its status as a mandatory item; short dresses for dancing and the city appear, trousers and shorts for sport, suits for work.

The flappers of the 1920s with their straight dresses, bare arms and calves, and short haircuts embody a new ideal: a woman who sets her own pace, earns money, has fun, and makes choices.

Further on — Chanel suits and those of other designers, soft knitwear, a dress in which you can work, travel, and live in a real city, not only in a salon.

All these steps do not abolish dress codes but redistribute them. What was once considered provocative — a short haircut, trousers, the absence of a rigid corset — gradually becomes the language of modernity. But strict boundaries remain: where a woman in trousers is "bold and stylish" versus where it is "too much," who is permitted to be athletic and "boyish" and who is still offered a long skirt and a hat.

In the end, modernity becomes a new form of propriety and a new framework for evaluation

If the 19th century established the image of a "respectable person" in a dark suit and a neat dress, the early 20th century adds another layer: being modern. A straight silhouette, a shortened hem, a simple palette, comfortable shoes, knitwear, geometric patterns, the absence of superfluous decoration — all this begins to be read as a sign of "a person of their time."

From the outside this looks like liberation: fewer rigid constructions, more movement, less gold, more function.

Inside — a new system of expectations: women are encouraged to be active, dynamic, but without stepping beyond the bounds of "good taste"; men — to look functional and "sporty" without losing control or status.

Dynamism in art and clothing fuses into a single criterion of modernity: a fast silhouette, clear form, a minimum of superfluous details seem visual proof that a person is "keeping up with the times."

The free movement of the eye across the painting and across the figure in clothing begins to work the same way: the more easily the gaze glides over an image, the more mobile, dynamic, and therefore current the person themselves appears. Those who by taste, age, or means do not fit this rhythm increasingly experience themselves as outdated, even if their actual life has not become any worse because of it.