The 19th century — a time when the world accelerates, and the eye learns to trust not only the "correct drawing" but also how everything looks at a specific moment

On the canvases of Turner, Delacroix, Courbet, Manet, Monet, Degas, Cézanne, and Van Gogh, reality becomes mobile: smoke, fog, electric light, crowds, work, leisure. The painting increasingly resembles not a report but a fixed impression: this is how it looks now, from here, to this person.

The Impressionists and Post-Impressionists do not smooth everything into a single "correct" tone: a quick visible brushstroke instead of a "polished" surface, color broken down into adjacent warm and cool patches, pure spots, reflections, shadow color, unusual angles and cropped frame edges, working from nature under changing light. White on a dress or shirt is no longer simply a "light tone" but a mixture of highlights, sky shades, and storefront reflections. As a result, the viewer perceives not only what is depicted but the very moment of seeing — as if looking together with the artist, not after them.

Color works as a trace of light and a nerve of time

The palette still relies on earth tones, lead white, mineral blues and greens, and organic reds. But new chemical pigments of the 19th century are added: chrome and cadmium yellows, bright greens based on copper and chromium, violets and pinks, synthetic ultramarine instead of rare lapis lazuli. They provide cleaner, more "saturated" shades that do not fade as quickly, and importantly — they become cheaper and more accessible.

Plus, the very form of paint changes: factory-made oil paints in tubes can be taken along, opened, and used to paint directly outdoors, not just in the studio. Artists go out to the river, the boulevard, the café, and begin selecting color not from memory but according to how it looks here and now. This makes painting more mobile: the palette responds to fog, smoke, electric light, and the changing sky almost in real time.

Textiles and dress code: factories sew the image of respectability

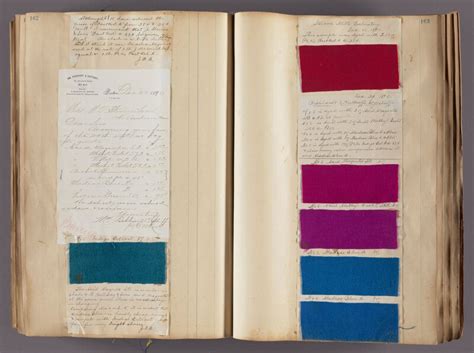

In textiles, aniline dyes from coal tar appear: dresses, coats, shawls, and umbrellas begin to glow with new violets, magentas, and blue-greens. The eye lives at this heightened level of brightness and contrast — and painting and clothing together expand the notion of how "loud" color can be in everyday life.

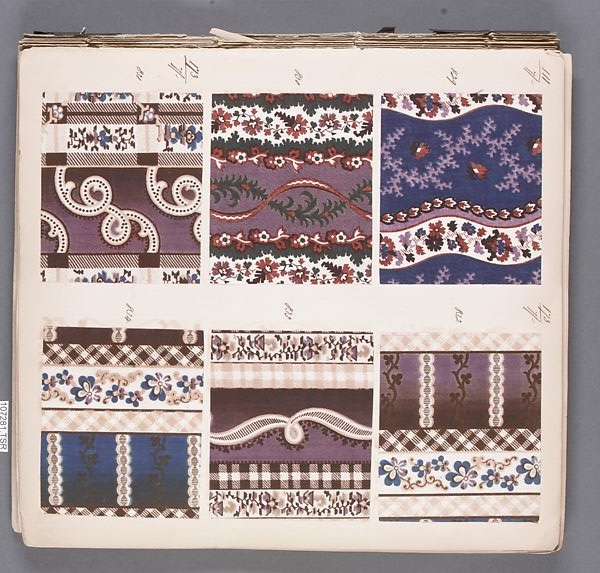

Spinning and weaving machines, cheap cotton, large factories — fabric becomes mass-produced. Ready-made clothing appears, standardized patterns, shops, display windows.

Fabrics also diverge toward opposite poles: machine-made lace, cotton, and inexpensive prints make the "urban" look more accessible, while silk and elaborate finishing still show how much labor and money are invested in a single outing.

The old sumptuary laws, meticulously regulating dress code according to status, position, and situation, fade away

Their place is taken by unwritten rules of "proper appearance."

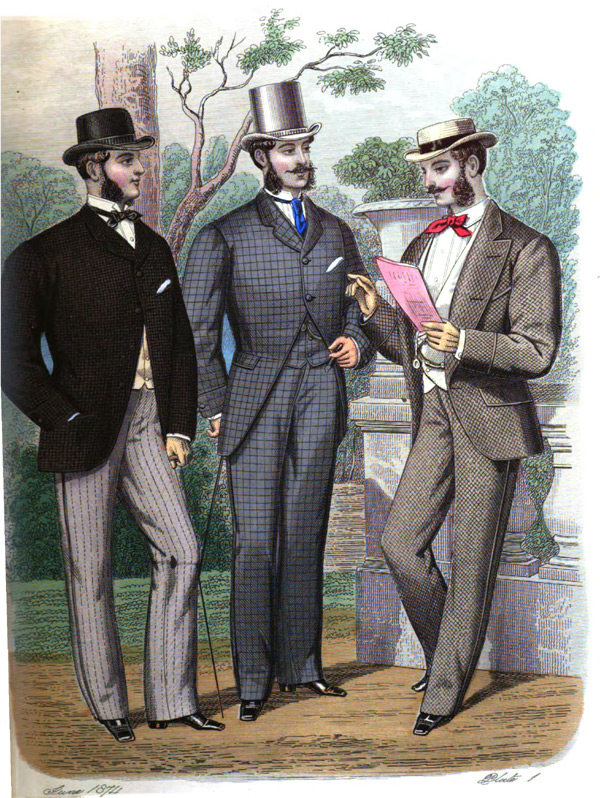

Early in the century, Beau Brummell invents a new masculine ideal: a dark, almost ascetic suit, impeccable cleanliness of linen, perfect cut instead of gold and lace. Since then, it seems as though moral qualities are inscribed in that neat dark silhouette.

For men, an almost universal costume is assembled: dark jacket, waistcoat, trousers, white shirt, tie, hat. Black, dark blue, and gray signify seriousness and reliability; color retreats to details — the tie, waistcoat, pocket square. Workers, clerks, and military men each receive their clearly legible uniforms. Against the backdrop of bright factory textiles, the serious dark suit becomes not only the norm but a contrast to the "too colorful" street.

In women's clothing, the body is constantly reassembled

The female silhouette changes radically several times over the century. After the freer Empire style come crinolines with enormous round skirts, then bustles shifting volume to the back, then another restructuring of the waist, shoulder, and sleeve line. In almost all variants, a corset is present: the degree of tightening is debatable, but the very idea of a "supported" body is considered obligatory for a respectable woman.

At the end of the century, costumes for sport, cycling, and work appear, as do reform dresses without rigid lacing, but each step toward freedom of movement provokes debates — from doctors to moralists.

In the end, a respectable appearance ceases to be a guarantee, but the habit of trusting it remains

The dark suit and light dress in paintings by Monet or Degas seem a transparent sign: before us are "normal" city dwellers with stable lives. But by the end of the century, the same silhouette can be bought in a ready-made clothing store and worn over very different biographies — from banker to clerk, from heiress to governess. The eye continues by inertia to read this image as proof of trustworthiness, even when it has become merely a carefully sewn shell.

Factory production and ready-made clothing bring a new idea: if you try hard enough and invest in the right costume, you can "catch up" with those who stood higher by birth. Purchasing becomes akin to inner self-improvement: you seem to "improve your character" through an improved jacket and dress. Conversely, the inability to afford the necessary item generates not only financial but existential feelings of inadequacy: as if something is wrong with you yourself, since you do not look "as you should."

The 19th century leaves behind a tricky situation: clothing still promises order and a reliable character behind it, yet technically already allows one to transform into a "respectable person" in cut and color without changing either origin or actual position.

Next part of the project - Early 20th Century: Form in Painting, Movement in Clothing