The 16th century is the moment when discoveries accumulated over previous centuries come together into an especially precise system

Artists work like well-trained image engineers — Leonardo, Raphael, Michelangelo, Titian, Veronese, Bronzino, Dürer, Holbein assemble a painting as a system.

In workshops, the full cycle is refined:

drawing by the rule of perspective, construction of space along vanishing lines, body anatomy by proportions, cartoon → transfer to wall or canvas, then layers of paint. Oil matures with Leonardo and Titian: glazes, soft tonal transitions, sfumato.

One can plan a complex multi-figure scene and be confident it will come together — with correct depth, logic of light, and recognizable materials. Stone, wood, fabric, leather, metal are no longer simply indicated but shown so that the viewer senses the difference.

Color in this system becomes a more controllable tool

The palette still relies on ochres and earths (sienna, umber, and others), lead white, charcoal, natural blues and reds. Until now, saturated blue in painting most often meant either very expensive ultramarine from lapis lazuli or the more opaque azurite — and was used in strictly defined places: the Virgin's mantle, the Holy Heavens, specific sacred accents.

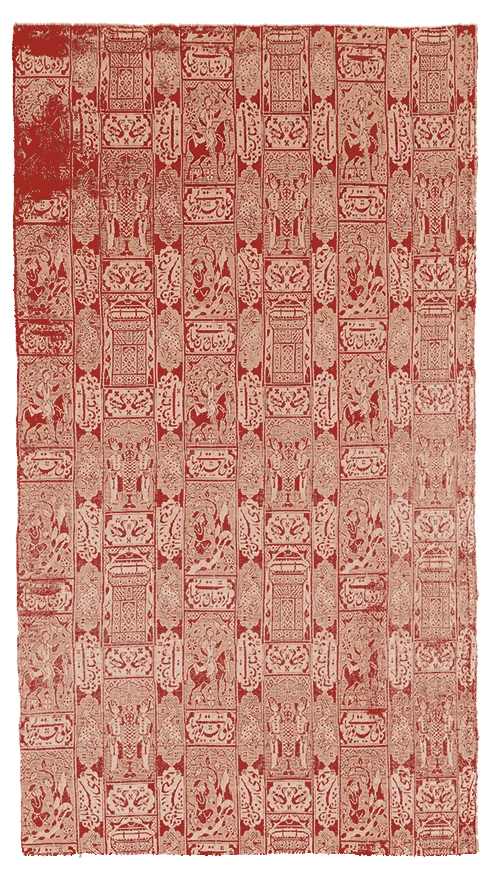

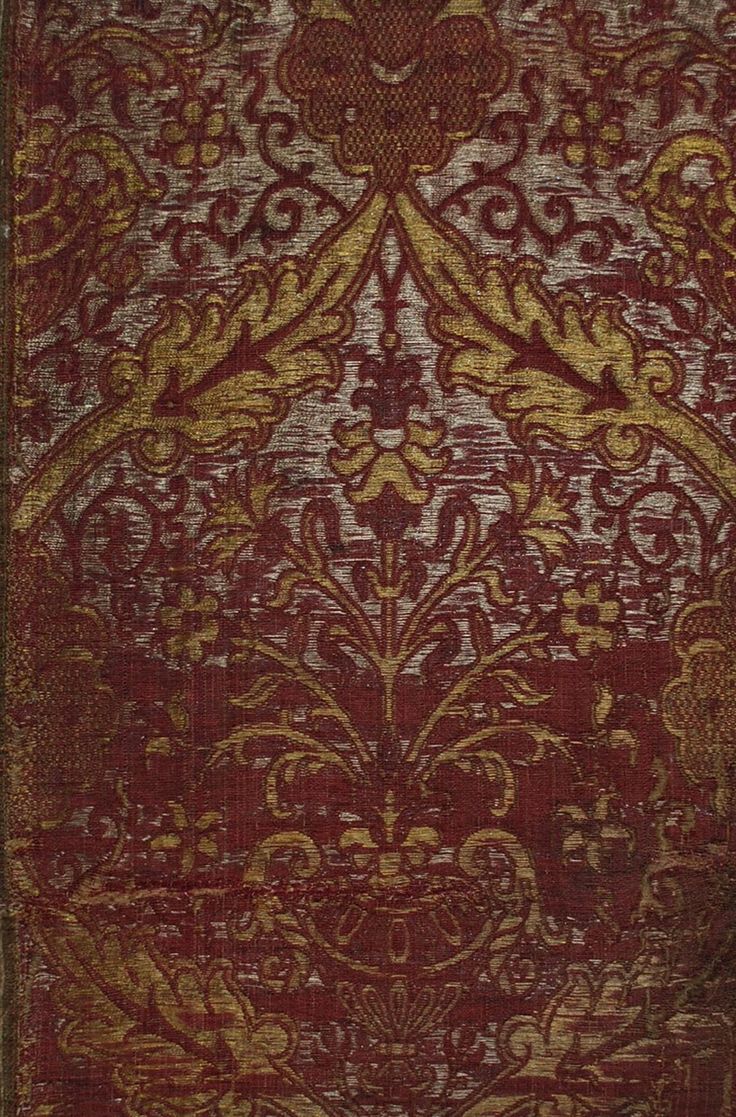

But in the 16th century, new bright dyes for fabrics arrive more actively through trade — the same cochineal for red and overseas blues like indigo, which give denser, deeper shades on dresses and mantles. Artists see these colors around them no longer as a rare exception but as part of the court and urban wardrobe, and gradually bring them into painting: blue begins to work not only as "celestial" and ecclesiastical but also as a fashionable, status-bearing, courtly color.

Red can simultaneously be ecclesiastical and courtly, blue — both Marian and fashionable, black — both about severity and about expensive fabric. The color scheme becomes more subtle and calculated: masters already know how to construct not only form but also the mood of a scene through combinations of tones.

Simultaneously, textiles and clothing begin to live a more nervous life

Fabrics become more diverse, trade broader: fine wools, velvet, silk, decorated with weaving and embroidery. Plus the first cotton chintzes, the first truly mass-produced patterned fabrics. They allow not only displaying wealth but also playing with appearance.

As a result, cities and states stamp out ever more sumptuary laws: some prohibitions for fur, others for certain silks, still others for jewelry and slashes on sleeves. The reason is simple: prosperous townspeople and new elites begin to dress almost like hereditary aristocracy, and by clothing it is no longer so easy to tell who was "born" and who "rose."

In women's fashion, the silhouette becomes more rigid and graphic: bodices are increasingly reinforced, the waist is tightened, chest and shoulders are framed by a square or oval neckline, skirts expand through petticoats and frameworks. In different regions, their own versions of the "bell-shaped" figure appear — Spanish and Italian variants, early frame constructions under the skirt. Hair is more often tucked under caps and elaborate headdresses, exposed neck and décolletage are regulated not only by taste but by rules. Women's costume becomes a field of negotiation between modesty, status, and display of the body.

Around this same time, the word "fashion" becomes established in European languages

It is needed to name a new sensation: tastes and silhouettes change more noticeably and rapidly than before, people no longer merely submit to hierarchy but invent, experiment, compare themselves with others. The growth of consumption, the anxiety of authorities, and the surge of sumptuary laws go hand in hand with the appearance of this word, which effectively denotes the acceleration of taste and a new game of self-expression through clothing.

Clothing at this time is still read at a glance, but that glance now errs more often

The way artists carefully learn to assemble space, body, and light into a controllable system resonates with inner experience: if a painting can be planned step by step, then one's own image can also be designed. A new thought emerges — that appearance is no longer only fate and duty but also an area of personal work: how you "assemble" yourself is how you will be read.

By cut, color, and trim, a person can appear higher in status than they are; some consciously construct their image through costume. What would later be called self-fashioning appears: the sartorial image is no longer only office or estate but also a chosen role — scholar, court humanist, austere jurist, merchant with ambitions.

Next part of the project - 17th Century: The Theater of Light in Painting, Baroque Costume as Role