The archetypes of Carl Gustav Jung and Carol Pearson share a common idea — identifying stable psychic structures that manifest in human behavior and perception. Yet they are far from identical, although they are often conflated.

Therapy is the process of letting go of the illusion that someone else knows how you should live your life.

Lisa Nepiiko, psychotherapist and trauma therapist

Jung arrived at his system of archetypes through the analysis of dreams and spontaneous imagery from his patients. Beginning around the 1910s, he observed and documented in his work that many of these archetypes recur across different individuals and influence their feelings, decisions, and motivations. In this way, he identified universal figures reflecting emotional and psychological patterns common to all humanity.

Later, Jung's successors began examining archetypes through the lens of Greek mythology. James Hillman, a leading figure of the post-Jungian school, proposed in his major works of the 1960s and 70s that we view the individual not as a unified "self," but as a constellation of active forces — archetypes akin to mythological gods. Images of gods and goddesses became metaphors for the inner forces and principles operating within a person. These mythological figures allowed for more precise descriptions of how inner motives manifest in behavior, relationships, and social life. The gods embodied specific energies — from unconscious impulses to one's role in society — making Jungian theory more applicable in practice.

Another frequently mentioned Jungian analyst is Jean Shinoda Bolen. Both Hillman and Bolen worked with Greek myths. The difference lies in their approach: Hillman offers a philosophically imaginative, metaphorical, and metaphysical understanding of archetypes through imagination and myth, while Bolen, from the 1980s onward, emphasizes the practical application of archetypes and their concretization through psychological types and personality models.

Interest in archetypes shifted even more decisively toward practice — toward how these processes can be observed directly in life. Arnold Mindell, extending the Jungian tradition, developed in the 1980s the process-oriented approach, where the archetype is viewed as a living dynamic, manifesting in the body, movements, reactions, and interactions with others. This step made archetypal psychology applied: the unconscious became discernible not only in symbols but also in everyday situations.

Carol Pearson, in her first notable book "The Hero Within" (1986), pursued the applied path further and gradually developed her own system of twelve archetypes for personal development and leadership purposes. Unlike Jung's archetypes, which describe deep structures of the psyche, and unlike the mythological archetypes expressing inner motivation, Pearson's archetypes demonstrate how inner forces become visible in external behavior, actions, and personal style.

The works of Carol Pearson and Arnold Mindell focus on the external manifestations of the individual. Starting at this level is easier — it is more tangible and yields quicker results. But without connection to the inner layer that Jung described, external approaches prove ineffective and sometimes simply too primitive. To preserve depth, one should work not only with the applied models of Pearson and Mindell, but at least at the level of the gods — archetypes that connect inner meaning with visible manifestations.

The contemporary popularity of Pearson's archetypes has led to their oversimplification. They are often used as visual codes or marketing personas, detached from their psychological foundation, merely hinting at it. As a result, the connection to the original idea is lost: an archetype is a way to understand the inner dynamics of personality, which may play different roles at different periods of life, not always coinciding with a person's external image.

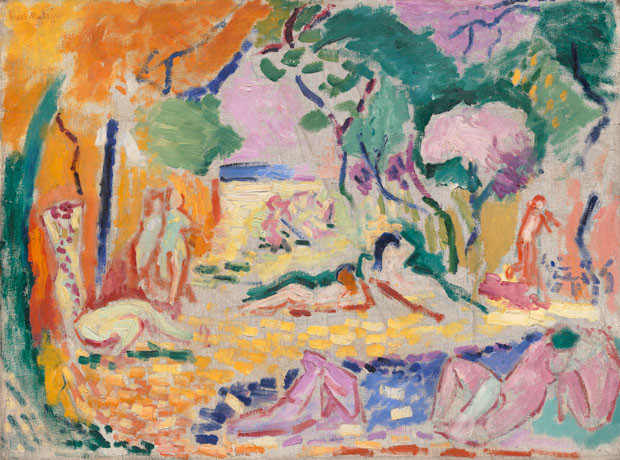

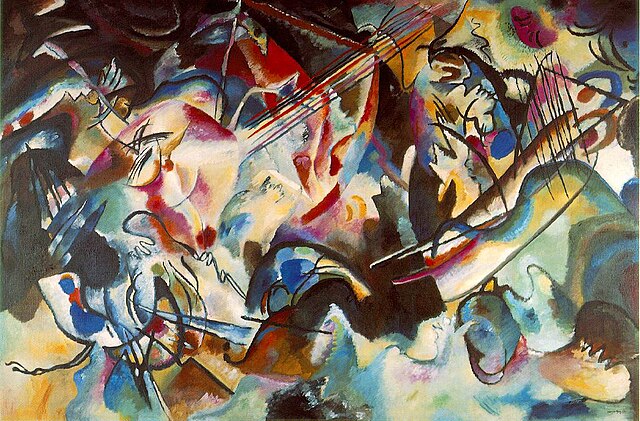

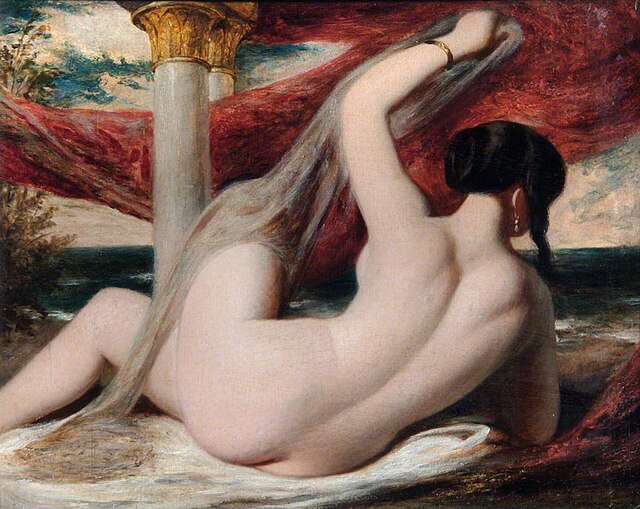

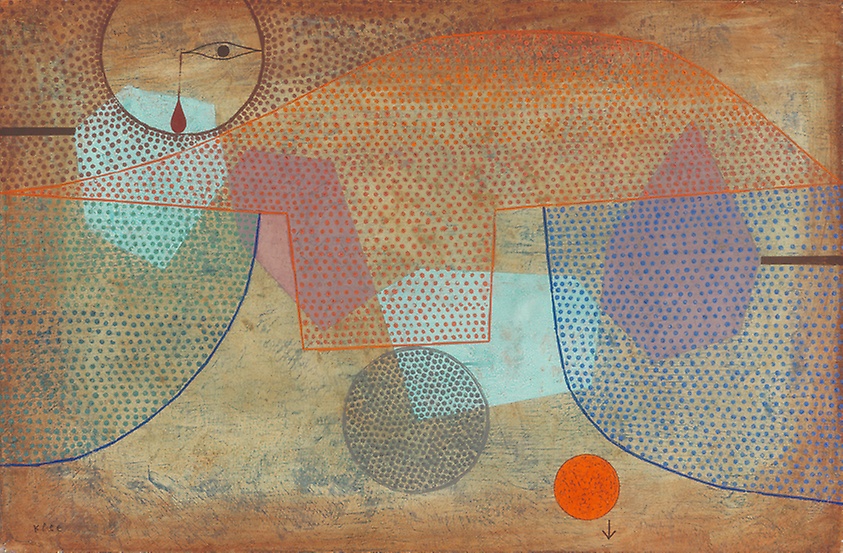

Put simply, we contain all archetypes — all 12, in Pearson's terminology. We possess the capacity to switch between them adaptively. Ideally, we employ different ones throughout our lives. Our appearance, face, and body are far less flexible than our psyche, requiring prolonged inhabitation of a given archetype before it becomes visible to others. Our creativity responds much faster to psychic changes. We more quickly express these changes in our drawings, clothing, and home environments. And now, in the age of virtual visual content, what we scroll and swipe through reveals far more about our inner state than how others perceive us.

It is precisely at this point that my approach continues Jung's lineage. Unlike most practices dealing with a person's visual manifestations, I begin not with the external expressions of archetypes — how you appear in my view or in the view of a group making guesses — but with their psychological content.

The inner archetypal component can be revealed through simple exercises: by choosing images that resonate or provoke resistance, a person manifests the internal structures of their personality. Working together, you and I will observe these manifestations, develop an understanding of your psychological matrix, and learn to see how it expresses itself in decisions, choices, aesthetics, and professional tasks. If desired, this work can continue in the direction of adaptive modeling.

This approach has numerous applications. In any sphere, including professional ones, you inevitably express part of yourself.

- In business, for example, this helps attract and guide clients, show who you are, what to expect from you, and also consciously support clients in their own explorations.

- For a healthy and productive atmosphere in a company, it is equally useful to understand who is who, and therefore what to expect — or conversely, what is impossible to achieve from subordinates or colleagues.

- Understanding yourself and others enables strategic, well-reasoned decisions. It is fascinating and intriguing to work with this process through personal style, space design, or projects for visual professionals.

Working with the visual, searching for yourself through your reaction to what you see — colors, patterns, textures, lines, space, and so forth — is deeply engaging and requires little exertion. And the results of this understanding and clarity you gain can be applied very broadly and in diverse ways.