What Does Science Tell Us?

The eye first catches the silhouette/form—the rough, "low-frequency" layer of the image: overall contour, proportions, where lines extend, where volume and support reside. It's like a rapid sketch: the brain needs to instantly assemble the whole before parsing particulars—the very principle of "forest before trees" demonstrated in classic scientific experiments with global and local forms.

Then luminance contrast emerges: where the darkest and lightest areas are, what captures attention from a distance—because fast visual channels are particularly sensitive to brightness contrast and large forms.

Only as a third layer do color nuances, fine patterns, and texture arrive: they require more refined analysis, often connected with details and color, functioning as refinement—adding the final intonation to the image.

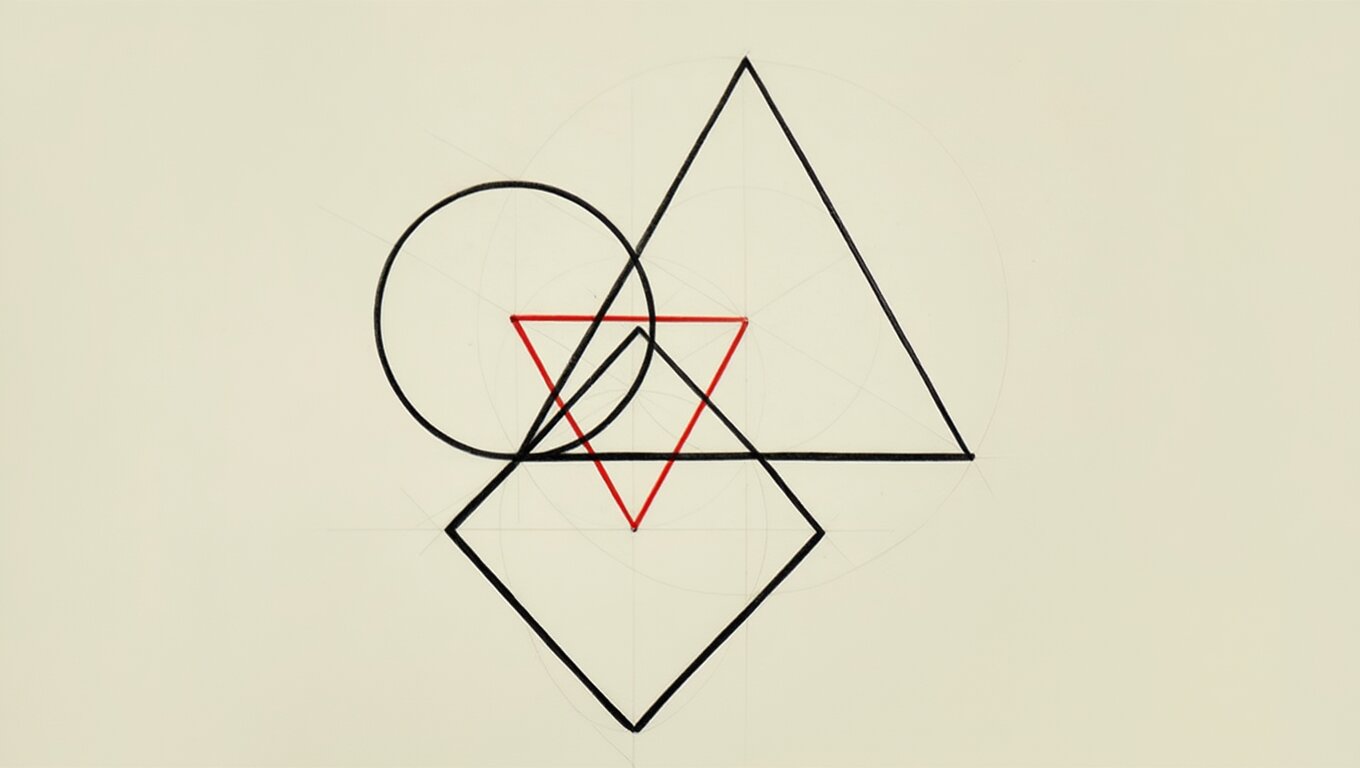

We usually discuss proportions as a technical task: what to lengthen, what to balance. But proportions have another layer—one of meaning. Large forms function as signs. Circle, triangle, and square are not mere geometry but three different ways of speaking about oneself through silhouette. Crucially, this operates at the level of the very first impression: before the eye has time to parse details, color, texture, and the quality of garments, it perceives the overall contour and reads the silhouette as a unified form.

Square (Rectangle): Earthly, Material, Constructed

The square is the most earthly form. It connects to what can be built, measured, divided into parts, and held. In symbolic language, the square represents house, city, order, boundary—a form that stands with stability. Thus it almost always reads as materiality, reliability, foundation, stability, weight, order, rationality, a sense of construction and control, structure.

This doesn't necessarily mean strictness of character. Rather, it's the sense that reality here is organized: there is a frame, there is a law, there is a plan. In clothing, this logic almost always manifests as the rectangle: a column, a sheath, a straight jacket, a coat with a clean front edge—any silhouettes that hold themselves through verticals and a clear boundary.

This geometry produces an impression of structure and control. It's less about the body and more about position: the contour establishes distance, composure, the status of form. The waist may be present here, but usually doesn't become the center of the composition—more important is the sense of framework: shoulders, verticals, straight lines, even hemline, readable fit. Practically, it always comes down to one thing: the silhouette must hold itself. Even soft fabric can work within rectangular logic if it has a clear contour and readable vertical.

The key meaning of rectangular logic: I am in the world of things and decisions.

Triangle: Thought, Intention, Ascension

The triangle is a form of idea and will. It has an apex: a point where energy converges. Thus in symbolic terms, the triangle connects with direction, activity, sharpness, aspiration, advance, striving, effort—sometimes with fire, not as romance but as movement upward and forward—with intellectual and volitional focus.

If the square says I stand, then the triangle says I strive. It is the form of thinking not as calm logic but as intention: to choose a target and gather forces toward it. This is why the triangle so often becomes a sign of the heroic, the strategic, the vectored focus—even when highly minimalist.

In silhouette, the triangle appears as an accent and a command to the eye: V-line, sharp lapels, a wedge, expansion downward or upward. It makes proportions purposeful: a where and why emerge, not merely how it fits. The point where lines converge becomes a node of meaning: that is where the decision gathers.

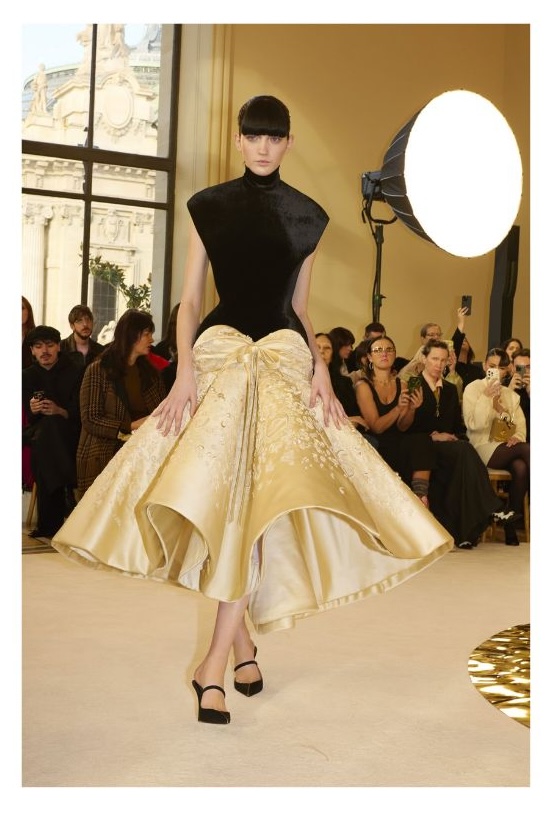

And a particularly powerful special case—the hourglass silhouette as two triangles meeting at the waist: the upper one from shoulders to waist and the lower from waist to hips. What matters here isn't the word femininity but the pure mechanics of form: two directed masses converge at a single point, and that point becomes the center of the composition. The eye naturally glides from wide to narrow and fixes on the juncture—the waist is perceived not merely as narrower but as the place of control and assembly. Psychologically, two triangles converging and pointing toward the center of the torso function as a symbol of aspirations, goals, and will directed toward the feminine portion, feminine destiny. For the viewer, this creates a balanced and purely feminine silhouette that typically reads as pronounced physicality and attractiveness: the image appears more alive, more feminine in the cultural sense, more confident in its physical presence, and more oriented toward connection.

The key meaning of the triangle: there is a goal, there is a vector, there is gathered energy.

Circle (Oval): Divine, Cosmic, Whole

The circle is a form traditionally connected not with the earth but with wholeness. Sphere, orbit, sun, mandala, halo—in many cultures, the circle signifies what cannot be divided into angles and has neither beginning nor end. It speaks of completeness, softness, inner equilibrium, gathered harmony, centeredness, enclosure without rigidity, completion, autonomy. This is why the circle is often perceived as divine or cosmic—not religiously, but as the sense of something larger than ordinary everyday logic.

If the square concerns what is built by humans, the triangle concerns human effort and thought, then the circle concerns what exists as a whole unto itself. The circle has a strong center: it gathers attention inward rather than distributing it across corners.

In clothing, the circle is almost never literal: on the figure it almost always becomes an oval—an elongated circle that can be mentally traced as one continuous contour. Thus circular logic means a unified contour and the sense of an envelope: cocoon, capsule, rounded architecture of form, a single shape. And this can work in very different ways: the circle can be soft and bodily, but it can also be austere—like a hermetic form, like a wholeness that cannot be disassembled. Then it transmits an impression of unified autonomy: the image appears gathered unto itself.

The key meaning of the circle: center, wholeness, sovereignty.

How This Becomes Proportion

When these meanings become visible, the question of proportion changes. It's no longer only about balancing the figure but about choosing which layer of reality is activated in the silhouette.

Rectangle: earthly and constructed—boundaries, order, competence, framework. Triangle: thought and intention—vector, goal, tension, gathering toward the apex. Circle: wholeness and the greater—center, autonomy, completion, sphere of influence.

And from here one can assemble formulas: rectangle plus triangle = structure with vector, plan and action circle plus rectangle = wholeness held by framework, sovereignty without dissolution circle plus triangle = wholeness with direction, inner strength that chooses its target

Thus proportions become not correct but expressive: they begin to speak through the meaning of form before the viewer has time to examine the details.

Let's conduct a small visual experiment. Let's test how purely the alphabet of shapes functions: what is seen first in any image from the internet, and whether the silhouette can be reduced to one dominant form.